“I believe it takes a long time to be an architect, it takes a long time to be an architect of one’s aspirations… To become an architect professionally takes just overnight… but to feel the spirit of architecture from which one makes his offerings may take much longer.” Kahn, Pennsylvania Gazette interview, 1972

Origins

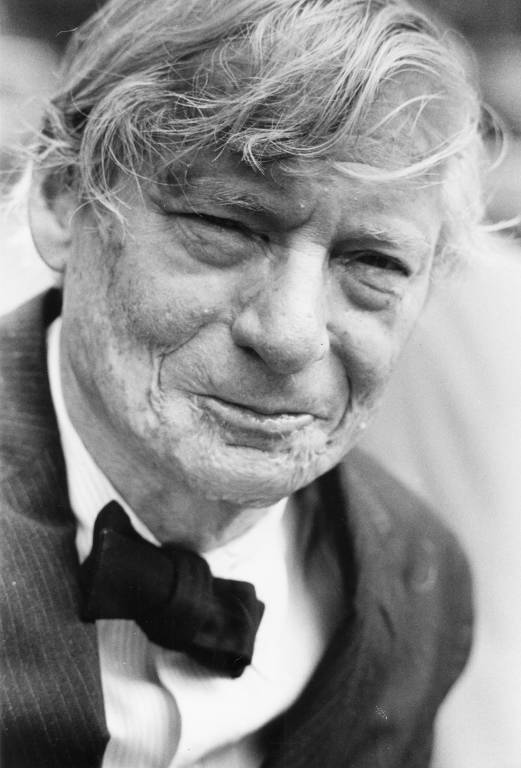

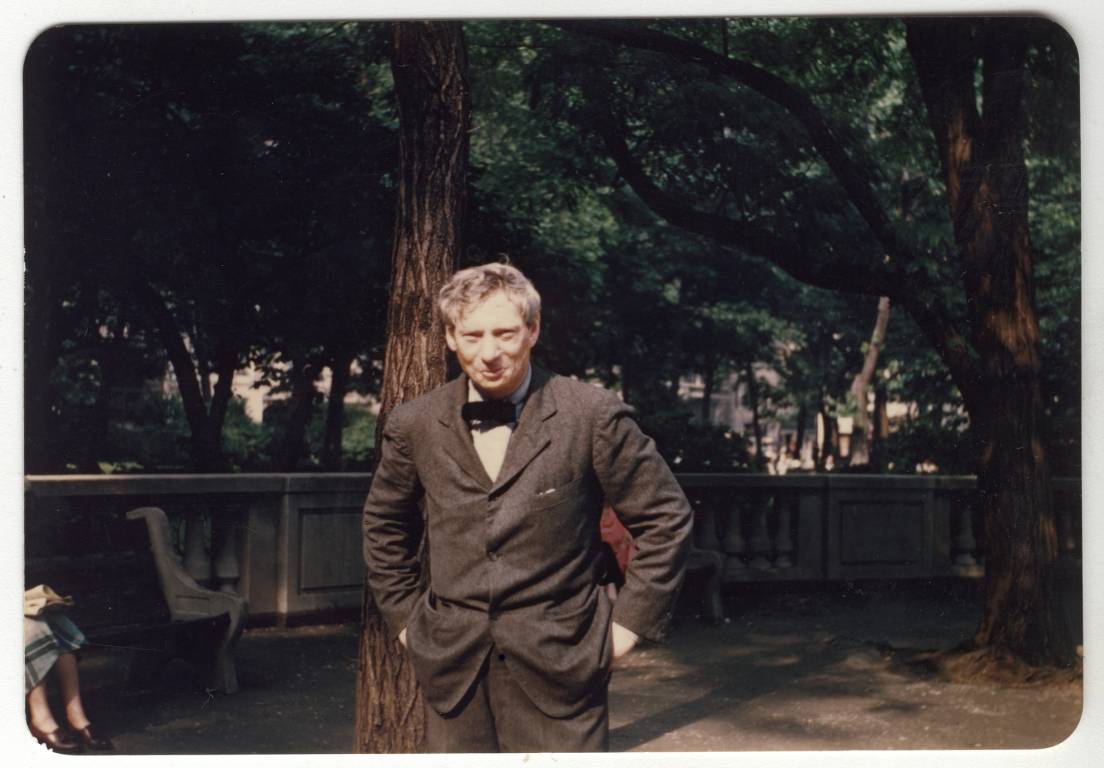

Louis Isadore Kahn’s life began far away from Philadelphia, the city where he would live and work until his death in 1974.

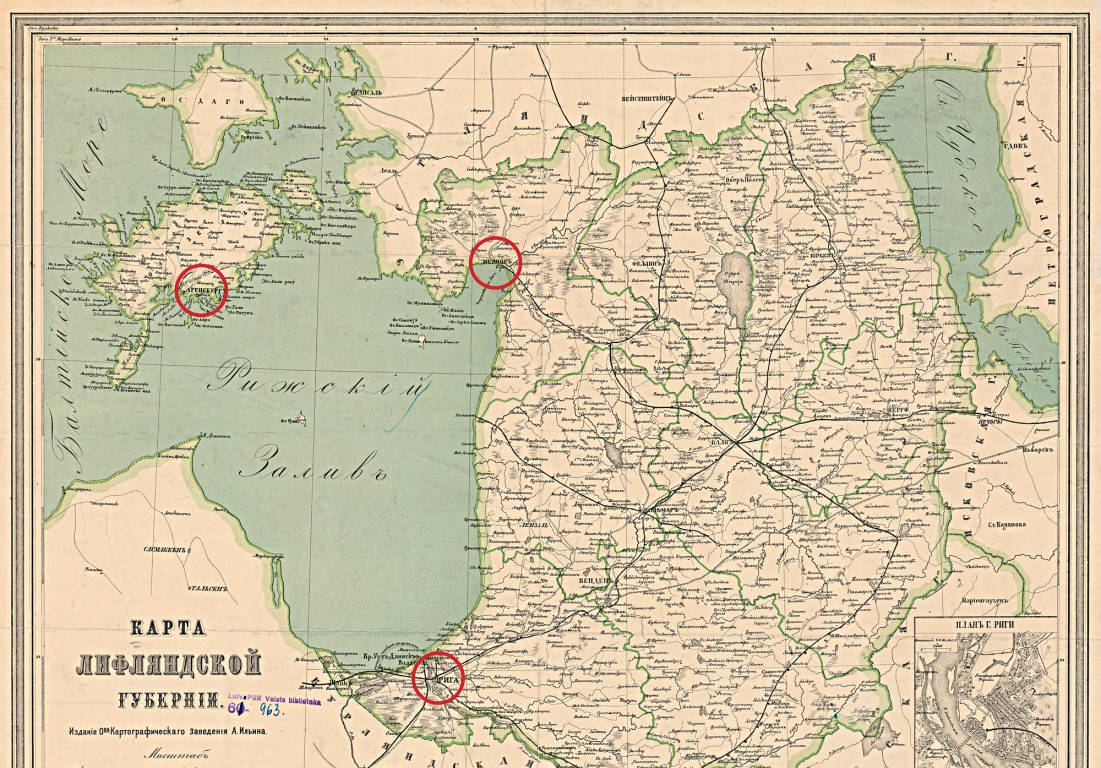

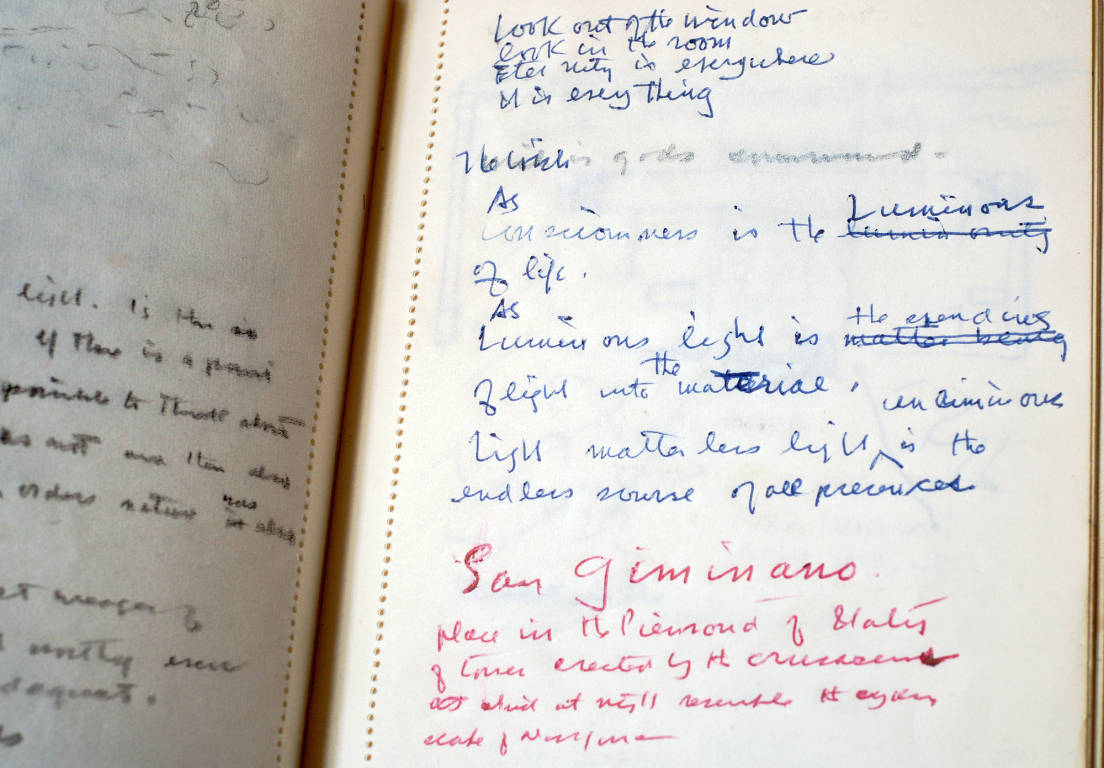

In 1901, he was born Leiser-itze Schmulowsky in Pernow, Russia (now Pärnu, Estonia). “I was born into the consideration of art as part of life, not something that’s attached to life in a peripheral way. My parents were in the middle of it.”1Kahn, comments on the Fort Wayne Fine Arts Center, Fort Wayne, IN 1961-65, Qtd in What Will Be Has Always Been: The Words of Louis I. Kahn, ed. Richard Saul Wurman (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1986), p. 10. Kahn’s father, Lieb, was a stained glass maker, drafted into the Russian army at the age of 17. He served Russia as a soldier, scribe, translator, sign-painter, and eventually a paymaster. Kahn’s mother, Beila “Bertha” Mendelewitsch, was a harpist from Riga. Both parents were Jewish.

During the winter of 1904, young Kahn survived a serious accident. According to family accounts, he was mesmerized by glowing coals in the fireplace and tried to carry them in his apron. The apron burst into flames, burning and scarring his face and hands. His mother claimed that the scars marked him for greatness. Kahn’s family, colleagues, and biographers would later discuss the marks on his face as an important part of his personal mythology: evidence of his early fascination with light, a social burden that shaped his self-perception, a possible source of his affinity for imperfect surfaces.2For instance: by Esther Kahn in conversation with Richard Saul Wurman, What Will Be Has Always Been and in Alessandra Latour’s L’uomo, il maestro (Rome: Kappa, 1986); by Yale colleague Vincent Scully, Jr. in Louis Kahn (New York: G. Braziller, 1962); by his daughter Alexandra Tyng, Beginnings: Louis I. Kahn’s Philosophy of Architecture (New York: Wiley, 1984); in his son Nathaniel Kahn’s 2003 documentary, My Architect. See also: Ole Bouman’s “Empowering Architecture” in Louis Kahn: the Power of Architecture, eds. Mateo Kries, Jochen Eisenbrand, Stanislaus von Moos (Weil am Rhein, Germany: Vitra Design Museum), 2013; David De Long and Brownlee’s Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1991); and Carter Wiseman, Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, A Life in Architecture (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2007)

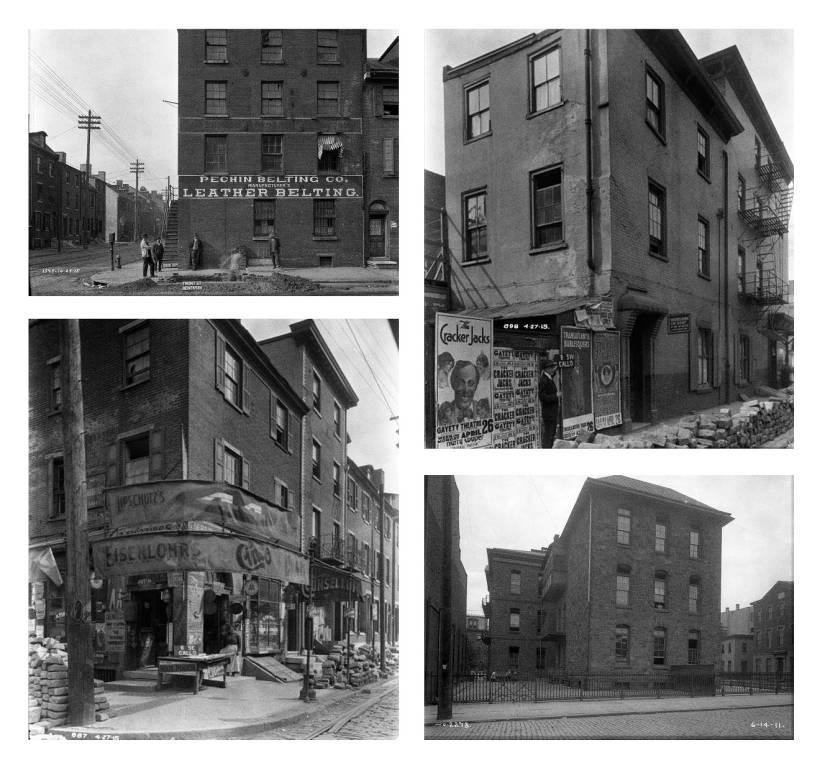

Lieb emigrated to the United States in June 1904. Beila moved with her two children (a third on the way) to the island of Ösel (now Saaremaa, Estonia), which Kahn would later claim as his birthplace. In 1906 the family emigrated to Philadelphia and reunited with Lieb, now calling himself Leopold Kahn (the surname became official in 1915). The family lived in Northern Liberties, one of Philadelphia’s industrial “river ward” neighborhoods.3See My Architect for evidence of how this section of Philadelphia’s landscape influenced Kahn’s work. Paul Goldenberger notes that “Nathaniel, who went to Northern Liberties in search of a personal connection to his father, seems to have come back with a scholarly insight.” (“Many Mansions: On the centenary of Louis Kahn’s birth, a look at his legacy. And his secret life,” The New Yorker, 12 November 2001, p. 130-1). A 1900 map of Philadelphia’s neighborhoods can be viewed here. They were poor and moved “constantly” over the next decade.4 The family moved 12 times in 13 years, according to William Whitaker (“Chronology,” In Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture, p. 22). Biographer Carter Wiseman estimates “seventeen times in two years” (A Life in Architecture, p. 16). In 1923, the Kahns seemed to settle for good in North Philadelphia, where they purchased a house on North 20th Street. But eight years later, the house was sold at a sheriff’s sale and Kahn’s parents moved to Los Angeles.

Scarlet fever delayed Leiser-itze’s enrollment in public school by a year. He was a shy student, sensitive to his low social rank as an immigrant “scarface,” but singled out by teachers for his artistic and musical talents.5 Wiseman, p. 16 His public schooling was supplemented by free extracurricular arts training: he won a spot at the city’s Public Industrial Art School, where his gifts were nurtured by Director James Liberty Tadd, a former student of Thomas Eakins and educational theorist in the Progressive Movement. He walked downtown for weekend art classes at the Graphic Sketch Club (now the Samuel Fleisher Art Memorial) at 719 Catherine Street, which he called “a place full of offerings.”6From Annual Report Text, Fleisher Art Memorial, Philadelphia, 4 December 1973, qtd in What Will Be, p. 243

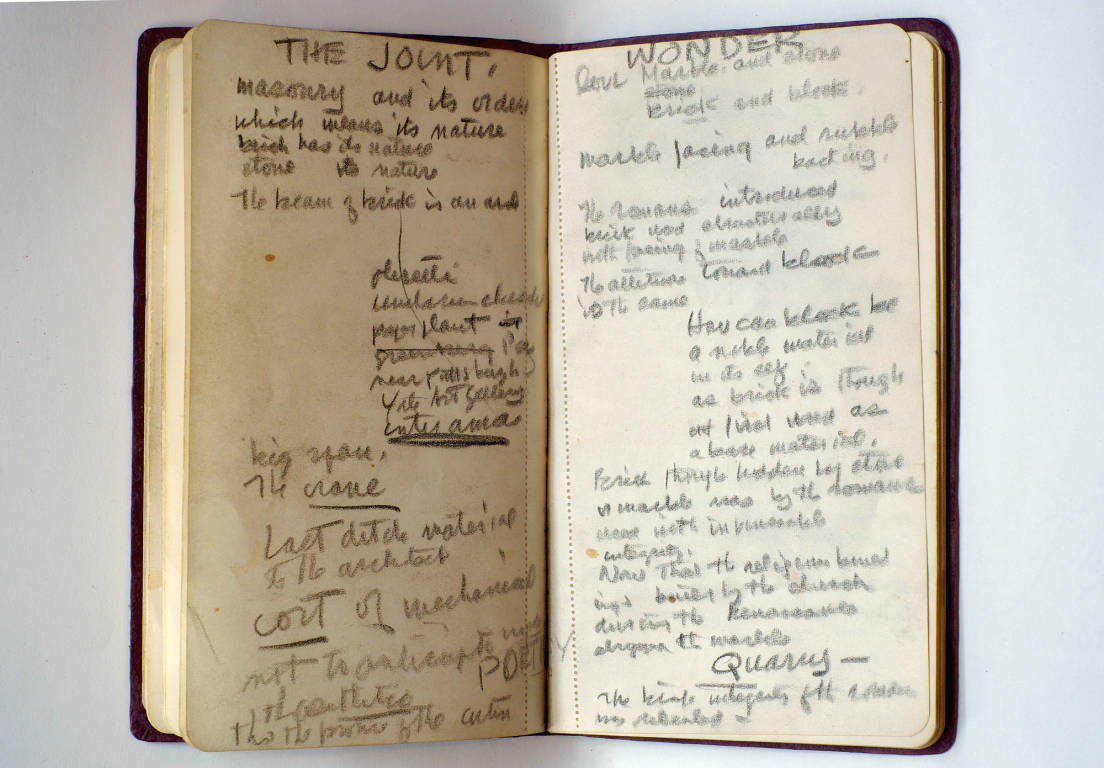

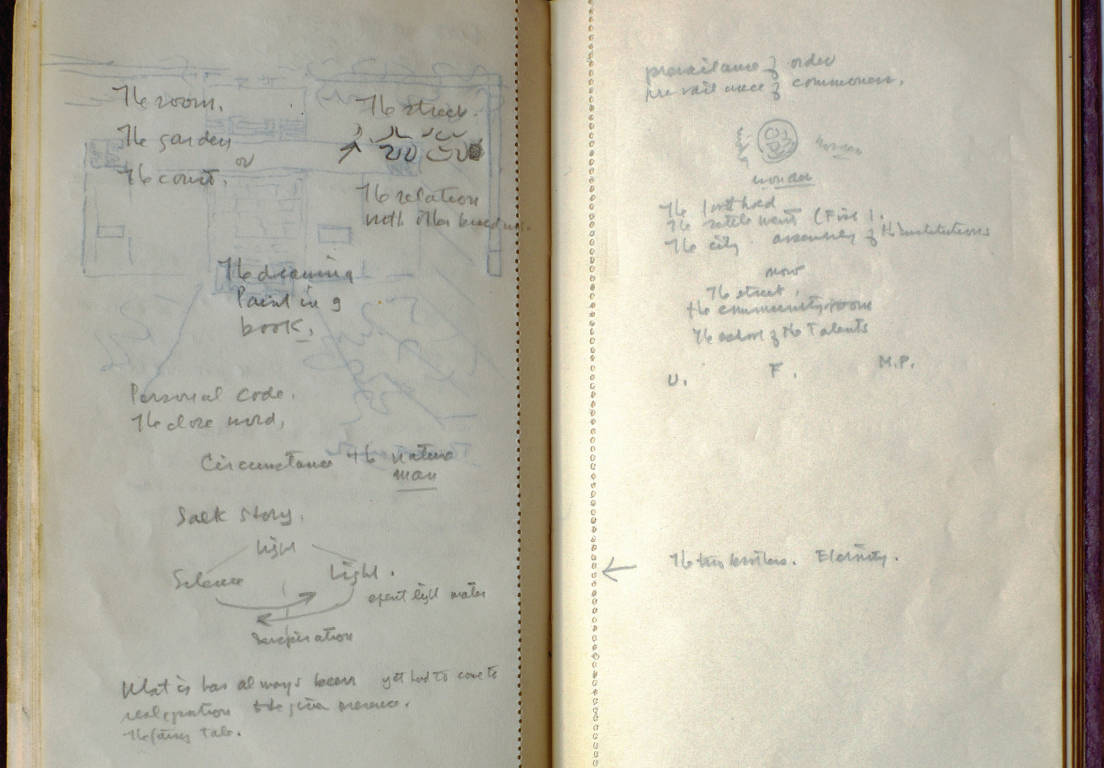

Everything changed in 1919, during his senior year at Central High School: he took William F. Gray’s course on the history of architecture. It “struck me between the eye and the eyeball,” he recalled.7“How’m I Doing, Corbusier?” An Interview With Louis Kahn. Pennsylvania Gazette, December 1972, p. 18 He abandoned his plans to study painting and, in 1920, began his freshman year in the University of Pennsylvania’s architecture program (then considered the best in the country). Paul Cret (1876–1945) headed the department, which he molded according to his École des Beaux-Arts training. The Beaux-Arts curriculum—a neo-classical, problem-solving approach to architecture—had a lasting influence on Kahn.

Kahn graduated from Penn in 1924 with a Bachelor of Architecture and the Arthur Spayd Brooke Memorial Prize bronze medal for “superior excellence.”8 Whitaker, “Chronology,” p. 22 He worked in city architect John Molitor’s office, followed by a stint in William H. Lee’s firm. In 1928 he set sail for a year-long voyage through Europe, churning out sketches and watercolors and playing piano in cafes to help pay for his colleague Edward Stone’s supper.9See Whitaker, “Chronology,” p. 22-3, for complete itinerary and notes; piano playing story retold by engineer and longtime Kahn collaborator Nick Gianopolis in What Will Be, p. 277. This was a familiar activity: in high school, Kahn helped support his family by playing piano and (later) organ in two neighborhood movie theaters, running between them to catch back-to-back shows. He recalled making slide “drawings which had to do with amusing ideas, funny people” that were projected during intermission. (From a conversation with Robert Wemischner, 17 April 1971, qtd in What Will Be, p. 121.) The fate of one of the theaters where Kahn played is detailed here by Harry Kyriakodis (“Poplar Theatre Renovated for Performing Arts,” 7 August 2012, Hidden City Philadelphia)

On August 14, 1930, he married Esther Virginia Israeli, a graduate of Penn’s psychology program who worked as a neurologist’s research assistant. The couple lived with Esther’s parents in West Philadelphia for the next 37 years. In 1940, they welcomed a daughter, Sue Ann.

“What will be”

At the time of his death, Kahn was working on ambitious projects in multiple countries and recognized as one of the most important architects of his time. His involvement in what he called “the marketplace” of architecture was less successful: only a fraction of his projects were completed while he was alive, and his office was $464,423.83 in debt when he died.10 This figure comes from Whitaker, “Chronology,” p. 28. Kahn mentioned “marketplace” during a lecture at the University of Cincinnati, 3 May 1969: “Most buildings that are built belong merely to the marketplace. That doesn’t belong to the realm of architecture at all” (qtd. in What Will Be, p. 73). But the work that was completed left an indelible mark on the world, and influenced generations of architects. In the decades since his death, Kahn’s legacy has proven to be profound and enduring.11One example of an early attempt to take stock of Kahn’s legacy: In 1984, Paul Goldberger described Kahn as a “transitional figure” who “provided the philosophical base for much of what is now going on in the development of architectural thought.” But according to Goldberger, he also belonged to the past: “It is not that his reputation has gone down since his death; there has surely been no figure in American architecture to replace him as a powerful maker of new forms, as an almost religious giver of truth. It is more that the idea of that kind of architect seems, for our time at least, to have died with Kahn at that sad moment in New York.” (“Louis Kahn’s Vision Now Belongs to History,” The New York Times,29 April, 1984).

He began his career during the Depression, which limited his opportunities.23However: a year-long engagement in Paul Cret’s office (1929-30) allowed him to work on multiple projects, including the Folger Shakespeare Library. See Whitaker, “Chronology,” p. 23-4, for a summary of his work during the ’30s. De Long and Brownlee suggest that “along with financial hardship came an unusual kind of architectural opportunity: the chance to pause and come to a new understanding of the role of his art at a time of great social demand and new technical and aesthetic potential (In the Realm, condensed ed., p. 20) In 1932 he formed the Architectural Research Group to study urban housing and propose improvements. In 1935 he opened his own architectural practice, working from home. Public housing and urban issues would occupy Kahn’s attention throughout the 1930s and ’40s.24He was active in the American Society of Planners and Architects (along with many of the major progressive architects in the U.S.), chaired a mid-Atlantic regional branch of the Federal Public Housing Agency’s Architectural Advisory Committee, and was employed by both the Philadelphia Housing Authority and the US Housing Authority. In 1941 he partnered with George Howe and Oskar Stonorov to pursue government housing contracts. Together they built five workers’ communities (over 2,000 units) and wrote primers on neighborhood planning. MoMa took notice and included their Carver Court Housing Project (1941–43) in an exhibition called “Built in the USA.”25Read the original MoMa press release here. Howe left the partnership in 1942 to accept a government position in Washington; in 1947 Kahn split from Stonorov.

Through Esther’s connections, he began to receive commissions for private homes, the first of which was built for his friends Ruth and Jesse Oser in 1942.26See William Whitaker and George Marcus, The Houses of Louis Kahn (New Haven: Yale Press, 2013) and Yutaka Saito, Louis I. Kahn: Houses (Tokyo: TOTO Shuppan, 2003) for discussion of all of Kahn’s private homes. Kahn began teaching at Yale University in 1947, commuting from Philadelphia. The Weiss House (1947–50; winner of the AIA Philadelphia Chapter medal) reflected the influence of Kahn’s new associate, Anne Griswold Tyng, a Harvard-trained architect who studied under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Buckminster Fuller called her “Kahn’s geometrical strategist.”27Robin Pogrebin, “Anne Tyng, Theorist of Architecture, Dies at 91,” The New York Times, 7 January 2012. Their collaboration produced several buildings, most notably the Yale Art Gallery (1951–53; winner of the prestigious AIA Twenty-Five Year Award) and the Trenton Bath House (1954-59), considered two of Kahn’s breakthrough works. Their relationship was also romantic, although Kahn and Esther would remain married for the rest of his life. Tyng and Kahn’s daughter, Alexandra, was born in Rome in 1954 and wrote a book about her father’s life and work in 1984, Beginnings.28The book discusses Kahn’s development as a person and architect. Tyng also provided editorial guidance for What Will Be Has Always Been, edited and designed by Kahn’s former student, Richard Saul Wurman. Here Kahn’s speeches, interviews, and writings are preserved alongside Wurman’s interviews with Kahn’s family and colleagues. Anecdotes about his unusual grapefruit-eating technique and fondness for women’s roller derby are given space alongside his major creative ideas and seminal moments. In these pages we meet a familiar Kahn who speaks about silence and light, always in search of Truth—and a man so engrossed in reciting lines from Cat on a Hot Tin Roof that he fails to notice Jack MacAllister’s puppy chewing through his trouser cuffs. Wurman once said that everyone who had a relationship with Kahn knew a different part of him, like the parable of “the blind men and the elephant.” (Steven Korman and Richard Saul Wurman, ICA Series lecture, 12 June 1974, p. 11. Transcribed by the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania)

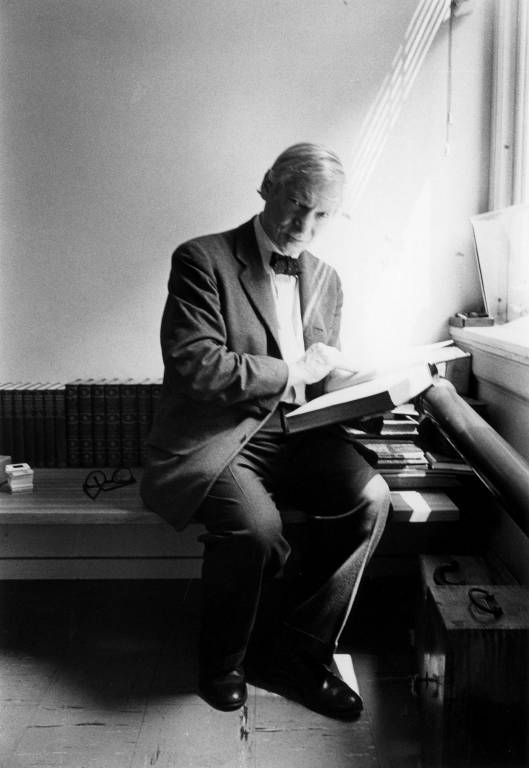

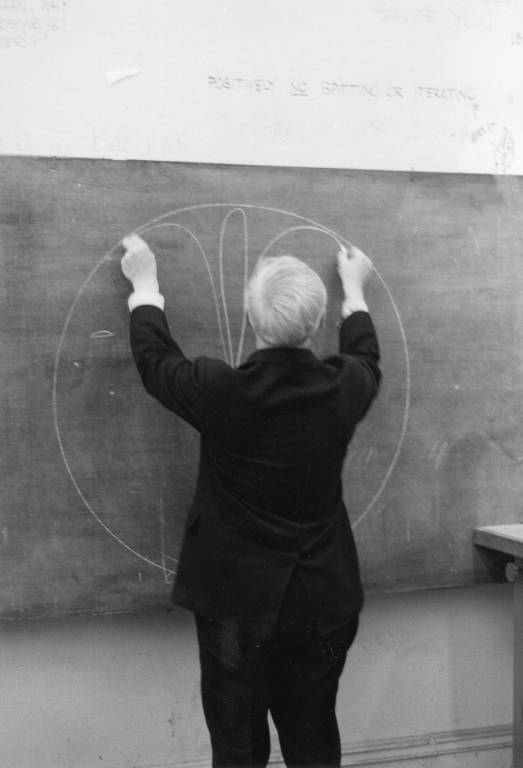

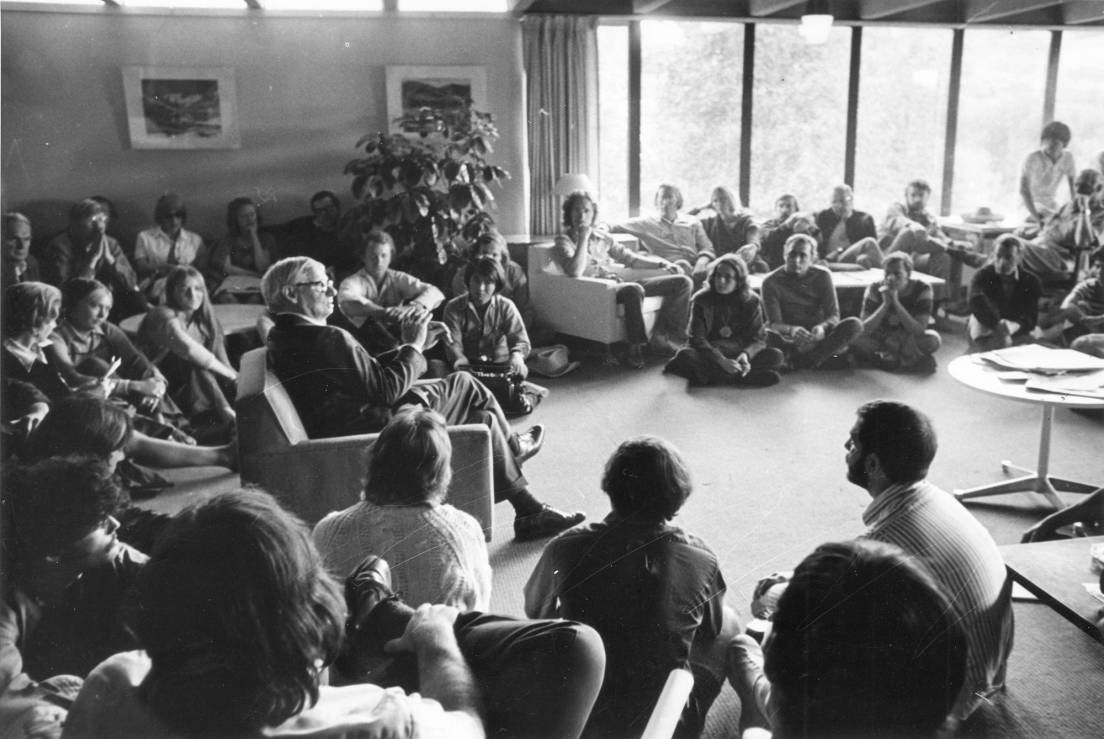

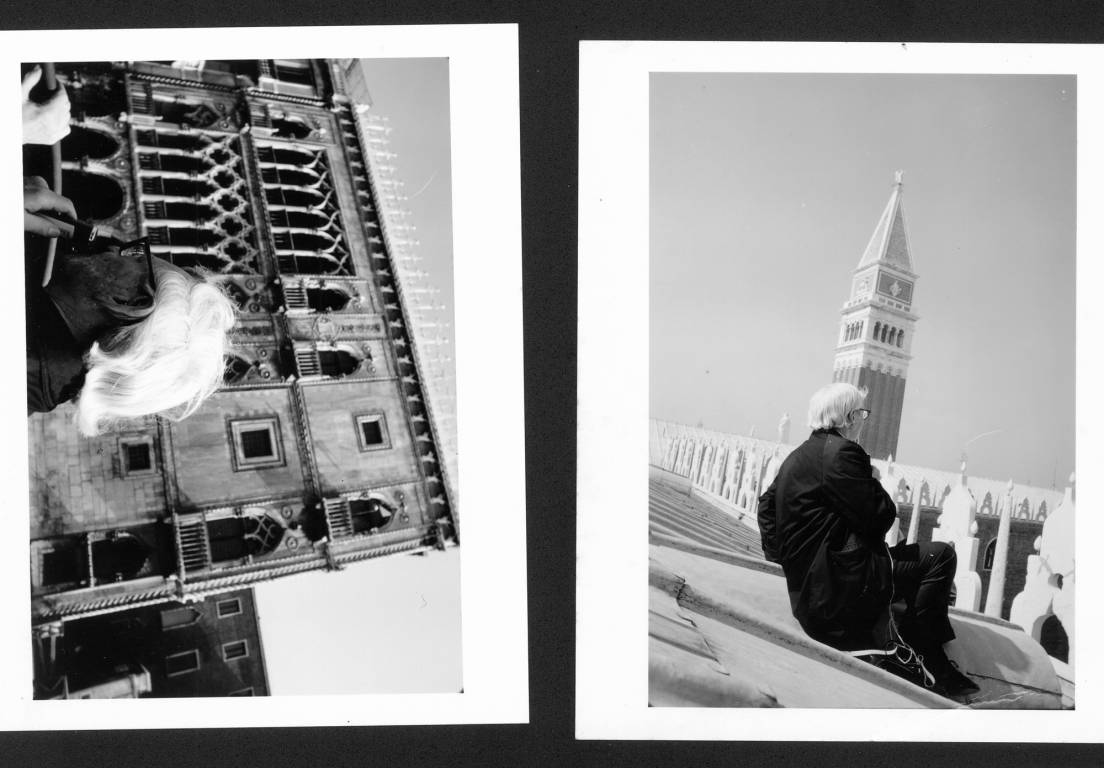

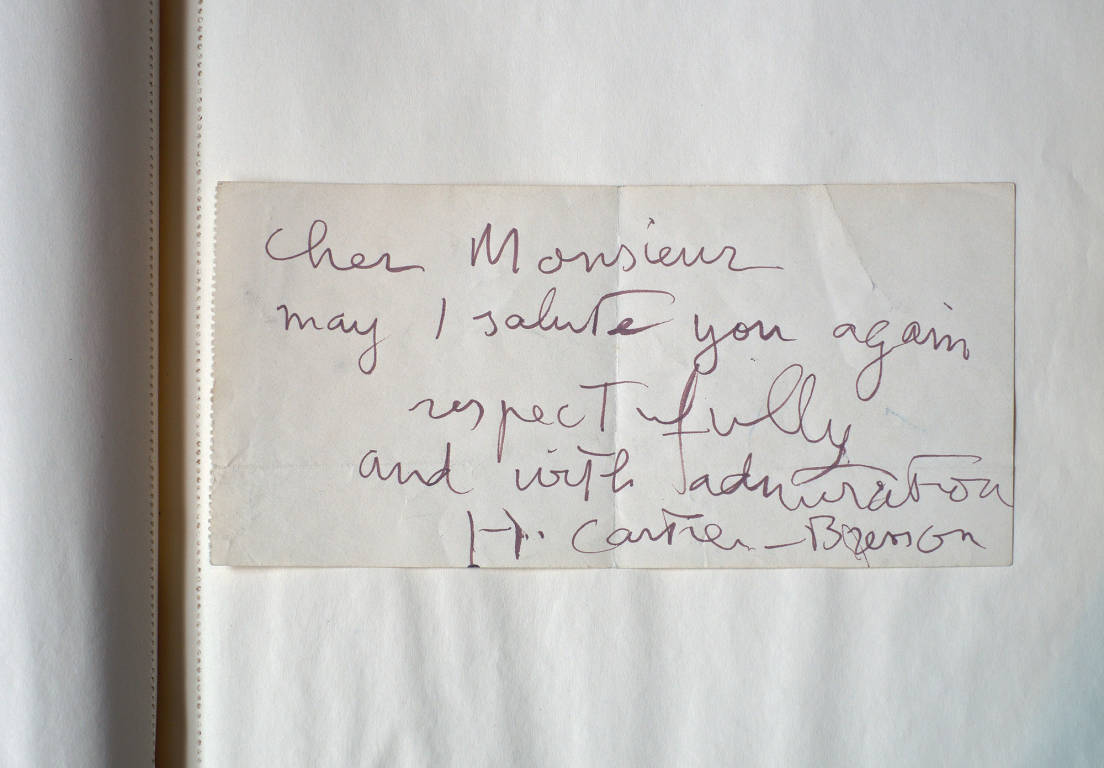

A 1951 fellowship to the American Academy in Rome gave him the chance to travel through Egypt, Greece, and Italy, where he observed ruins and natural light; many scholars agree that this trip’s revelations shaped his mature work. In 1955 he resigned from Yale and began teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, where he was an influential and beloved member of the faculty’s “Philadelphia School” until the end of his life.29Colleagues included Robert Venturi, Romaldo Giurgola, Robert Geddes, Ian McHarg, Robert Le Ricolais (Whitaker, “Chronology,” p. 26.)

His Richards Medical Research Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania (1957–1960) launched his international reputation. MoMa featured it as part of its “Visionary Architecture” exhibition and as its own solo exhibition. (“Kahn’s reluctance to credit Tyng signals their separation,” notes William Whitaker.)30 Ibid. De Long and Brownlee note that Tyng “remained associated with the office until Kahn’s death, her position evolving from that of employee to consultant” (Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture, condensed ed. (Los Angeles: Universe, 1997), p. 252, note 61

In 1958 he met Harriet Pattison, who later described herself as “a companion for his thoughts.”31Qtd in In the Realm of Architecture, condensed ed., p. 110. Pattison gave birth to their son, Nathaniel, in 1962, completed her studies in landscape architecture at Penn in 1967, and collaborated with Kahn during the final years of his life. In 2003, Nathaniel Kahn released the Academy Award-nominated documentary My Architect: A Son’s Journey, which brought his father’s work—and the story of his complicated family life/lives—to a wider audience.

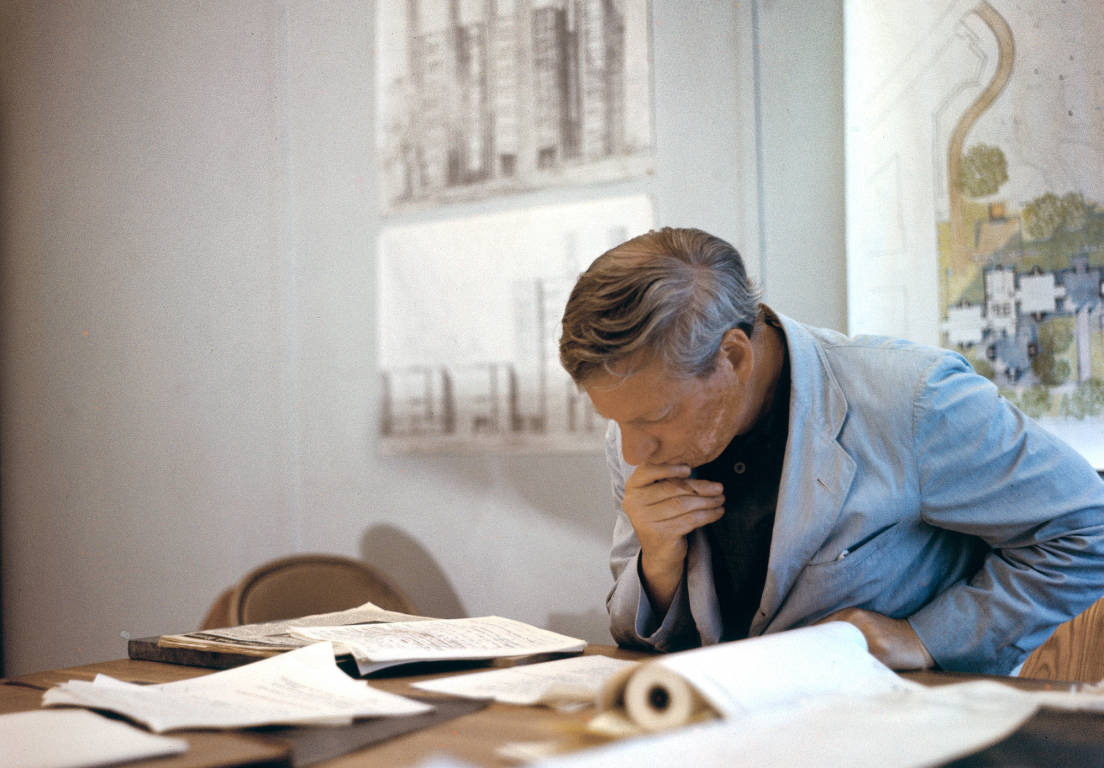

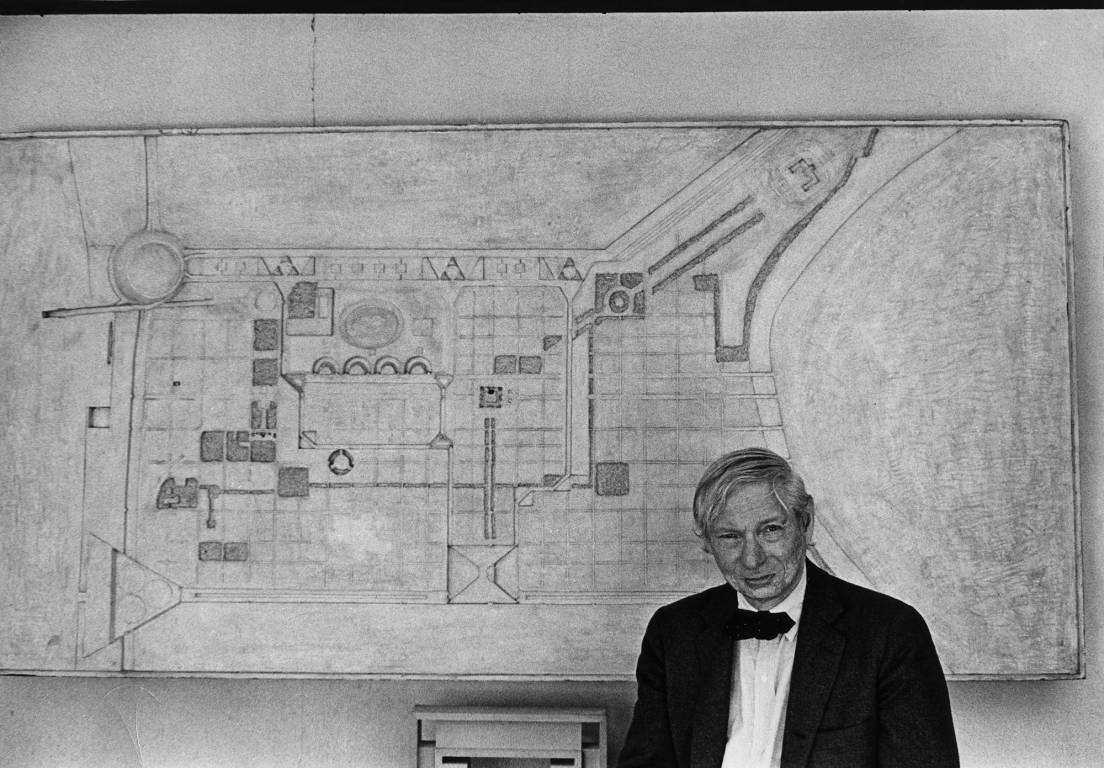

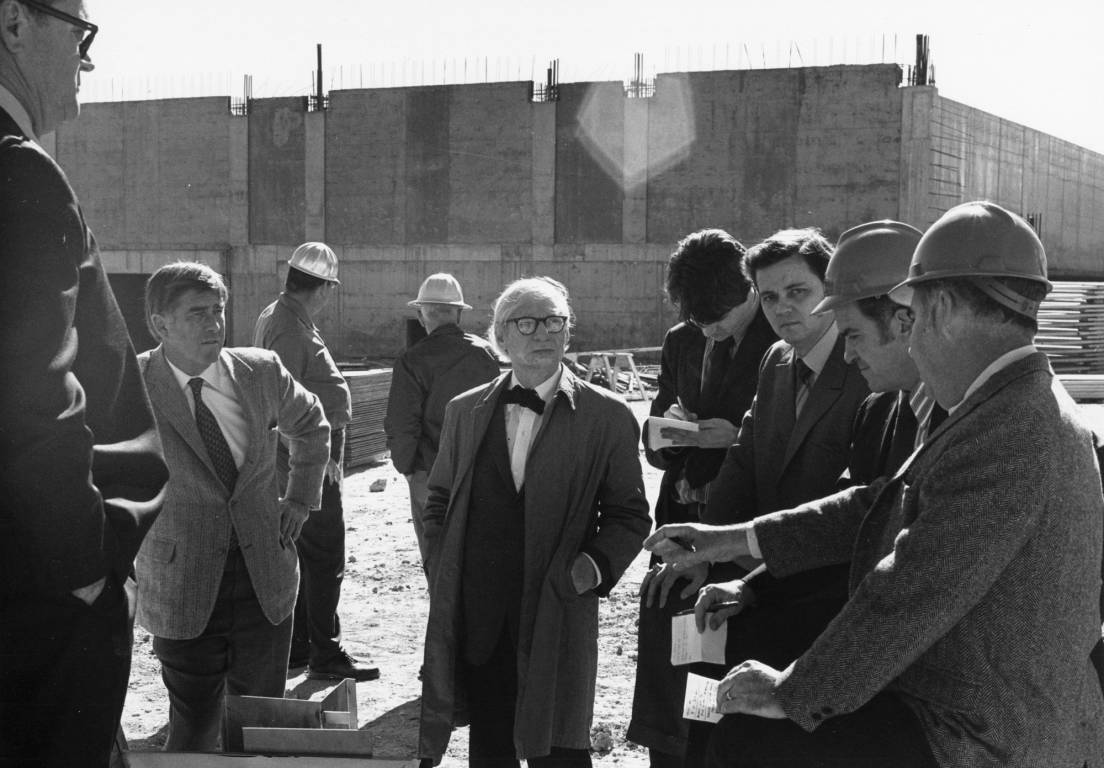

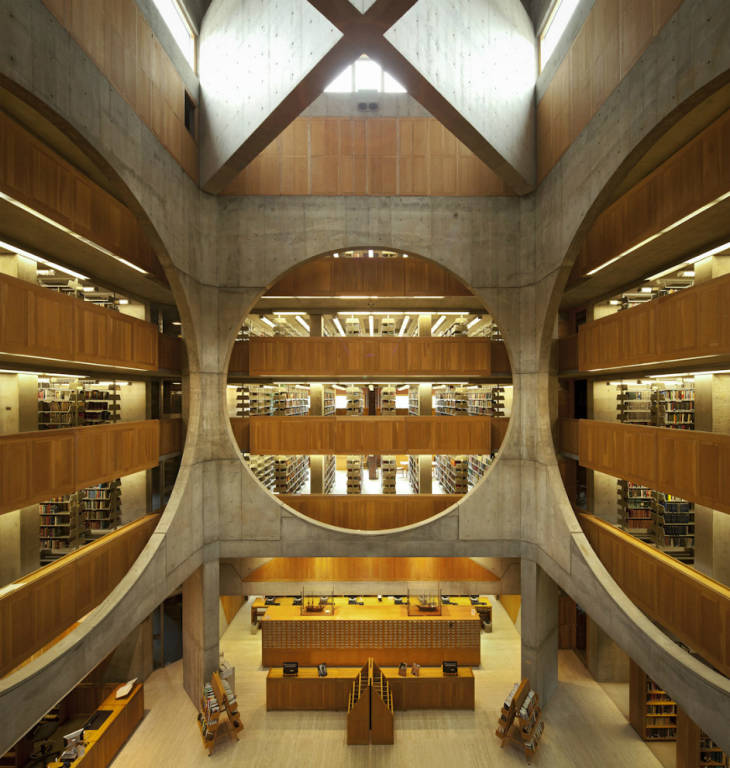

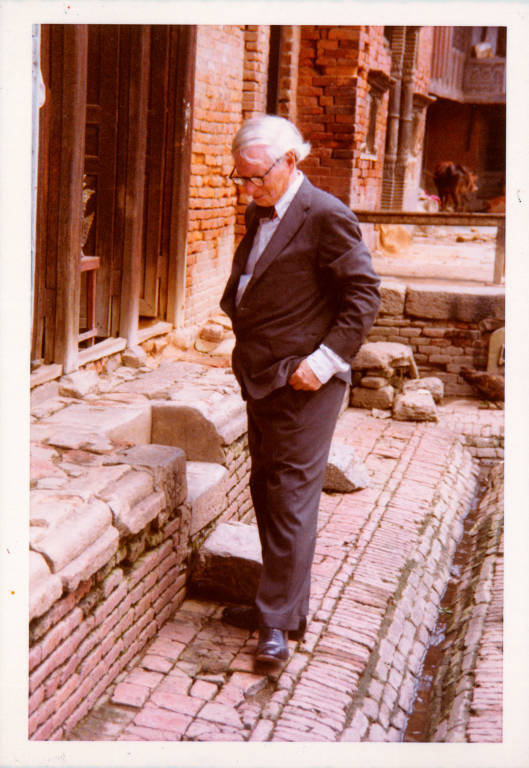

Many of the projects completed during the final decade of Kahn’s life are his best known: the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California (1959–65), the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas (1966–72), the Phillips Exeter Academy Library (1965–72), and the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, India (1962–74; he was inspecting construction work in India just before he died).32Countering the dominant narrative of Kahn studies, George Marcus and William Whitaker make the case that Kahn’s (largely overlooked) housing designs warrant the same attention paid to his late monumental works because “the design of houses was every bit as compelling for him, and as pivotal for his work, as the design of his other buildings.” They argue that “Kahn’s houses are difficult to grasp at once, for they were designed not as architectural manifestos but as buildings that express the circumstances of their creation.” They are “not demonstrative,” but they repay the effort that it takes to get to know them. (The Houses of Louis Kahn (New Haven: Yale Press, 2013), p. 2. Two more watershed projects—The Yale Center for British Art (1967–77), and the National Capitol of Bangladesh in Dhaka, Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan; 1962–83) were completed after his death. FDR Four Freedoms Park —“a room and a garden,” commissioned in 1973—was completed in 2012 (design and construction were carried out by David Wisdom and Associates in association with Mitchell/Giurgola Associates).33 Kahn discussed the room/garden idea in “Lecture at Pratt Institute,” qtd. in Louis Kahn: Essential Texts, ed. Robert Twombly (New York: WW Norton & Co., 2003), p. 268.

While returning to Philadelphia from India on March 17, 1974, Kahn died of a heart attack in the men’s room in Penn Station, New York. Because the address on his passport was (mysteriously) crossed out, three days passed before his body was identified. A New York Times obituary declared him “America’s foremost living architect.”34Paul Goldberger, “Louis I. Kahn Dies; Architect Was 73,” The New York Times, 20 March, 1974.

In an interview less than two years before his death, he said: “If you want to ask me what my best work is, I couldn’t really tell you. It would be, as many people express, what is not yet made, what is not yet expressed. I have the feeling that the greatest men died—terrible word—thinking that they have done nothing, judging from what lodges in them as the yet unexpressed.”35“How’m I Doing, Corbusier?” An Interview With Louis Kahn. Pennsylvania Gazette, December 1972, p. 26