“You can never build a home, because a home is made by the people.” Kahn, "Architecture and Human Agreement," 1973

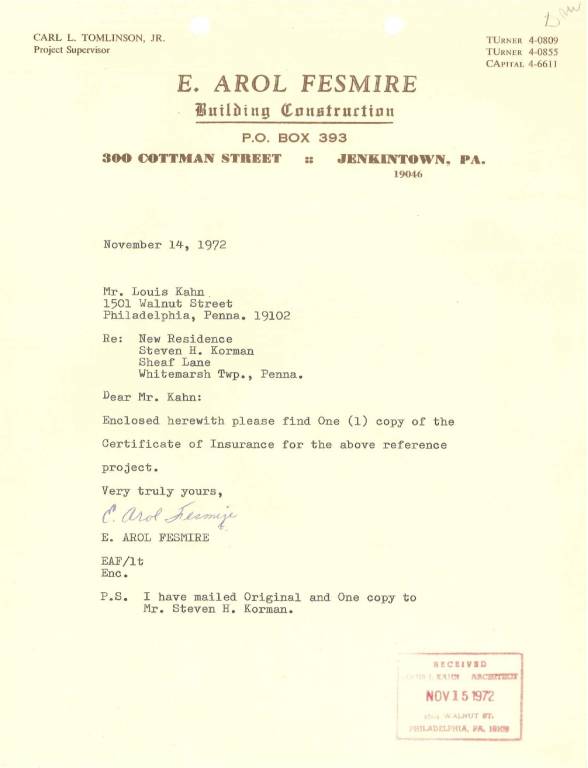

The Korman project began as a dual commission. Real estate developer Steven Korman and his sister, Lynne Honickman, approached Kahn about designing houses for their two families on adjoining lots in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, twenty miles from Philadelphia. The land was originally purchased as part of a 70-acre parcel through the Korman Corporation, a prominent local real estate company founded by Steven’s grandfather in 1909. When the commercial project fell through, the land was divided among the extended Korman family. Although the Honickman home was never built, design work began at the same time as the Korman project and continued until the spring of 1973.1 George Marcus and William Whitaker, The Houses of Louis Kahn, (New Haven: Yale Press), 2013, p. 223.

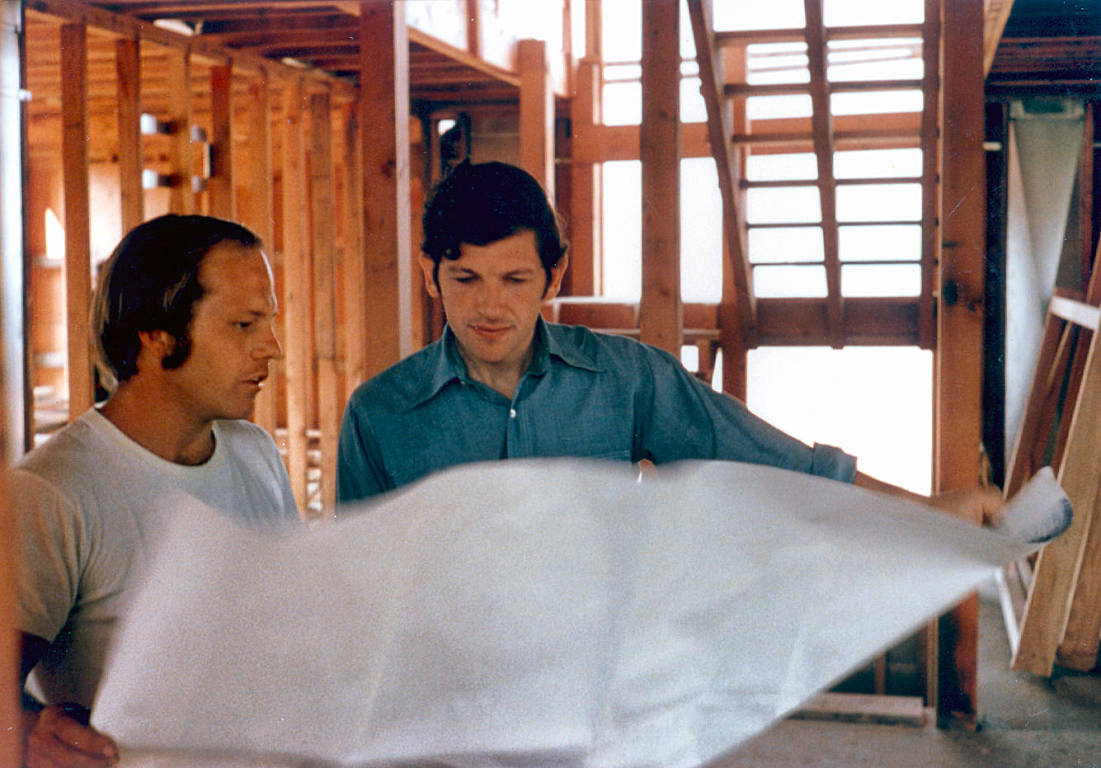

Steven and Toby Korman, then 31 and 29 year-old parents of three small boys, had long admired Kahn’s architecture. (Steven’s work with the Frankford Supply Company made him appreciate the way Kahn highlighted the beauty of materials.) He recalls approaching Kahn several times about the commission before he accepted. It is easy to understand his hesitation: Kahn was in his 70s and had risen to global prominence. He found himself increasingly busy with major projects such as the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh—an ambitious undertaking which began in 1962 and would not be completed until nearly ten years after Kahn’s death.2 De Long and Brownlee’s take: “During the years of demanding involvement with projects of almost unchartable complexity, the design of private dwellings may have offered Kahn some sense of relief.” (Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture, condensed ed. (Los Angeles: Universe, 1997) p. 190). Or perhaps Kahn would not have recognized such a precise distinction between monumental and domestic projects. In a 1972 lecture at the Aspen International Design Conference in Colorado, he said that “An architect can build a house and build a city in the same breath, if he thinks about it as being a marvelous, inspired, expressive realm.” (See “The Invisible City,” qtd. in What Will Be Has Always Been: The Words of Louis I. Kahn, Richard Saul Wurman, ed. (New York: Rizzoli, 1986), p. 151). To the Fort Worth Press, he described the Kimbell Museum as “a friendly home” (qtd in In the Realm of Architecture, condensed ed., p. 216). One of the 1940s city planning pamphlets co-written with Oskar Stonorov stated that “the plan of a city is like the plan of a house.” (qtd. in In the Realm, p. 32). Perhaps each of these statements suggests that despite the smaller scale of a housing plan, the human relationships and interactions that it contains (and enables) are no less mysterious or complex than the workings of a government, cultural institution, or city.

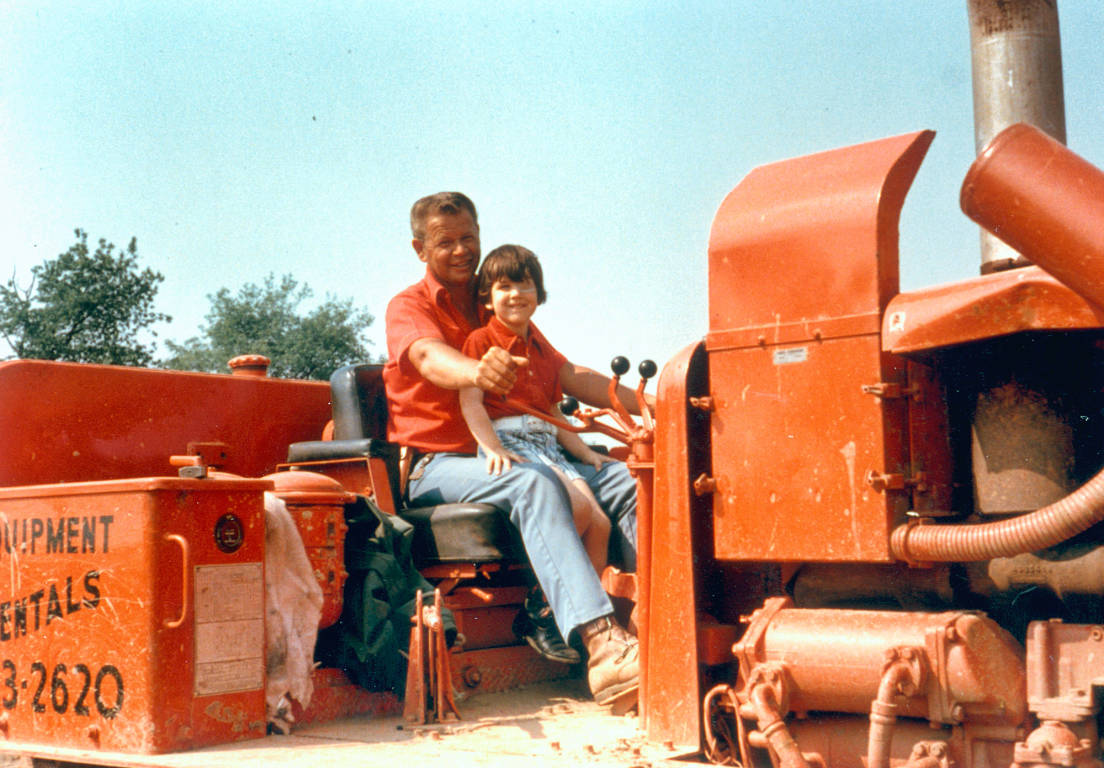

Landscape architect Harriet Pattison was initially surprised that he accepted the commission. She feels that his personal experiences influenced his decision to some degree: his own domestic life was complicated, and working on a family project was “healing.”3 For a full account of Kahn’s family life/lives, see My Architect, a 2003 documentary by Kahn and Pattison’s son, Nathaniel Kahn. He was intrigued and charmed by the Kormans, “these young people and their hopes.”

But the commission also represented a search for new architectural meaning: “It enabled him to go back to the beginning of architecture and to think about what the dwelling is, and what it might be, and to think about generations dwelling in the same place… It was a place to rebuild the world and get it right this time.”7Harriet Pattison, interview, July 2013

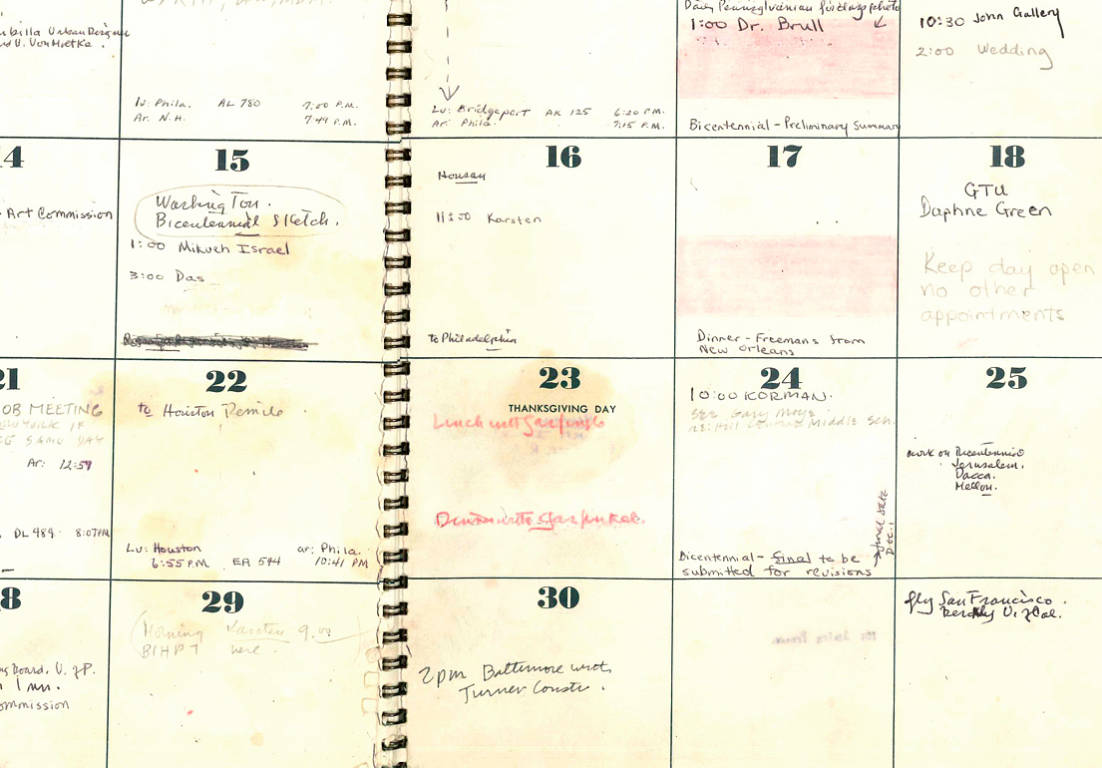

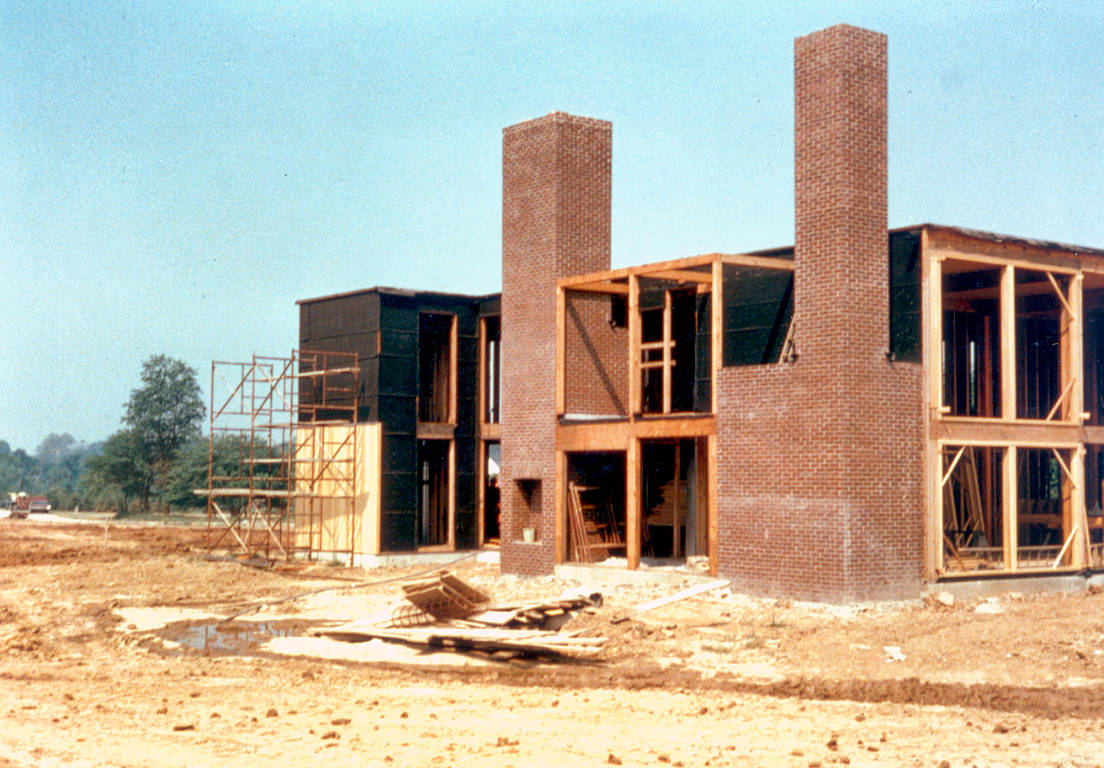

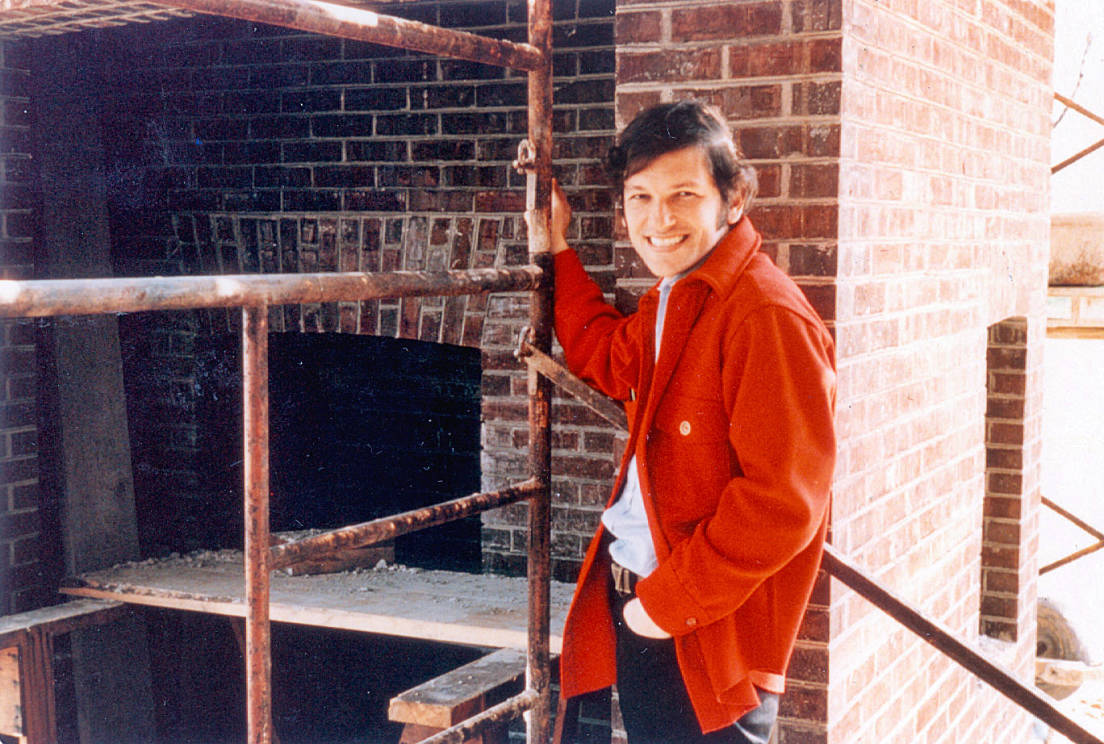

Kahn agreed to take on the two commissions and made his first drawings in May 1971. (The design process is discussed here.) Construction on the Kormans’ began in October 1972; the family moved in during the fall of 1973.

The project had its moments of stress—a chimney was torn down and rebuilt twice because it wasn’t up to Kahn’s standards. But in the end, it seems, Kahn’s belief that “joy will prevail” was borne out.8 “If you don’t feel joy in what you’re doing, then you’re not really operating. And there are miserable moments which you’ve got to live through. But really, joy will prevail.” (Lecture at Pratt Institute, 1973, qtd in Louis Kahn: Essential Texts, ed. Robert Twombly (New York: WW Norton & Co., 2003), p. 280)

“Everything was built here by hand,” said Steven in a 1974 Institute of Contemporary Art discussion, “and again as much as I thought I could read plans, I didn’t appreciate some of the details that Lou was able to deal with… we love living in the home, it’s a wonderful, warm house for us and we live in our living room, we live in the dining room, we live all over the house. It’s very special to us.”9ICA Series lecture, 12 June 1974, p. 18, Tape #62. Transcribed by the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania The Kormans’ deep involvement with the project—and the opportunity to get to know Kahn and his team—“changed our lives,” said Toby Korman.10 Interview with Richard Saul Wurman, 15 April 1974, p. 14, Tape #25. Transcribed by the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania.

Living in the house allowed the Kormans to learn from Kahn even in his absence. Those lessons continue today. In 1998, Steven and Toby’s oldest son, Larry, moved into the house with his wife, Korin, and their three children, and took on responsibility for preserving and renovating it.